Gastronomy as culture: the debut of the first course of the Alta Scuola Veronelli.

A vision of oenology and gastronomy as cultural products; an approach to cuisine, to wine, to the vineyard and to tasting that favours methods of research, critical examination, the assignment of meaning and value: the inspiration given by Luigi Veronelli, an eminent personality who observed and supported Italian agri-food production and quality cuisine from the post-Second World War period until the early years of the new millennium, is more vibrant now than ever, and the Scuola dedicated to him intends to bring together and share his legacy through training.

Today we are meeting Andrea Alpi, a member of the Scientific Committee and Educational Director of the Alta Scuola Italiana di Gastronomia Luigi Veronelli, gastronome, sommelier, Sensory Project Manager SISS (Italian Society of Sensorial Sciences); together with Andrea Bonini, director of the Seminario Permanente Luigi Veronelli and Coordinator of the Alta Scuola Veronelli. They will tell us about one of the latest initiatives promoted by the Seminario Veronelli, an association aimed at promoting the quality of Italian food products through the study and presentation of gastronomic culture. This is the first course launched by the Alta Scuola Veronelli, Walking through vineyards; places, people and culture of Italian wine, scheduled for the end of May at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice.

Taught over the period of one semester, until October 2019, it will examine Italian wine production, casting light both on the origin of a food system that includes cuisine and the gastronomic heritage, and the connections with the world of art and culture.

I asked Andrea Alpi, in detail, to whom the course is dedicated.

The Walking through vineyards course is dedicated to the owners and personnel of wine production companies, in particular those who work in marketing, communication and the sales sector; to operators in the quality food and wine trade; to the owners and staff of restaurants and wine bars; those involved in communications, such as journalists, bloggers and people employed in public relations; tourist guides and operators. Walking through vineyards is also aimed at university students on degree courses in wine production and oenology, food and catering sciences and technologies, tourism and cultural heritage sciences.

What are the prerequisites necessary to enrol on the course?

Applicants must have successfully completed an initial course in wine tasting, which is often provided by educational agencies such as the Associazione Italiana Sommelier and many others.

What skills will participants be able to acquire?

The skills that this course provides are linked to the six subject areas that make up the course: we cover highly operational skills, so specialisation with some of the major Italian tasters in the field of sensorial analysis, to skills of an economic order, since we will place specific focus on the wine markets. The wines of Italy and its territories will, of course, be at the centre: we will have a long exploration of the Italian wine districts. In addition, and this is one of the characterising elements, we have reserved as much as a third of the 180 hours of the course to matters or issues that would not be expected on a course dedicated to wine. Indeed, gastronomic culture will be a fundamental part of the course.

What subject areas will be explored during the traditional teacher-led lessons?

This is a course that has wine and the places of wine as the main focus. It will be more than an oenological journey through Italy; we will go walking though Italian vineyards virtually, but also physically, and so the oenological aspect will be the beating heart of the course. However, this will be accompanied by preparatory and in-depth aspects: tasting, knowing, which means also understanding what the territory is. Understanding the territory is a section that will be especially emphasised: from the location of the land to the composition of the soils but also the landscapes and everything that makes Italian wine a cultural aspect.

We have already talked about the areas understanding the territory and vineyards and wines of Italy; in addition to these, we will be covering the gastronomic culture, making use of the professionals and authorities on such matters within the Scientific Committee, starting, of course, with Alberto Capatti, who will also offer a digression on Italian cuisine, identifying the ten capitals that, due to their history and cultural and gastronomic importance, well represent the heritage of Italian cuisine. We will then place the focus on the communication of quality, that is, all those skills required to transfer the added value of these agri-food products to our interlocutors and a focus, already mentioned by Andrea, on the sensorial aspect and evaluation: we are not only talking about sensorial analysis, which will, of course, be an important factor of the training, but also all those skills that must be mastered in order to express a judgement in an accomplished way.

For completeness, I would like to ask Andrea Bonini to list in detail the subject areas that will be explored.

The first specialist course offered by the Alta Scuola Italiana di Gastronomia Luigi Veronelli has a study plan made up of the following subject areas: understanding the territory, vineyards and wines of Italy, gastronomic culture, Italian cuisine, communicating the quality, sensorial aspects and evaluation.

A teaching plan made up in this way fully reflects the multidisciplinary approach that the Alta Scuola wants to offer its students: indeed, we believe that the time of the hyper-specialists is over. Instead, it is necessary to succeed in coordinating different skills to restore the complexity and variety of the Italian wine production sector.

How much time will be given to tasting? Will there be experiential opportunities in the territory?

Tasting is a prerequisite but also a tool. It is a tool of exploration. In each of the 20 lessons that will be dedicated to the Italian wine-growing territories, an hour will be dedicated expressly to tasting, so on-the-spot tasting of wines selected on the basis of the territories explored but also based on the histories, the stories, the slant that the lecturers wish to give to their presentations.

Tasting will also be the subject of a specific course of sensorial analysis: the students’ senses will be developed and raised to a high level of awareness through on-the-spot tastings, not only of wine but also of essences, the actual aromas that can be the key to reading, for example, the main vines of Italy.

Is it possible to take the course without neglecting the professional activity or university studies?

The course has been put together precisely to meet the needs of people who study or work during the year. We have broken down the training into intensive weekends, around one a month during the semester; we then provide an opportunity of concentrated training in a single week in July, residential, as obviously the weekends will be, on the island of San Giorgio, at our base at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini. On that occasion, seven days of lessons will be offered, encounters with the wines, the producers, the experts and the lecturers.

We also have the option of combining the direct, traditional lessons with a part carried out as distance learning through the use of a dedicated platform specifically for this.

Who makes up the faculty?

For this first course, we have brought together a very large faculty, over 35 lecturers. More than the number, what is striking is the level of quality and the authoritativeness of those lecturers. We have oenologists and agronomists, university lecturers with a specific background in wine production and oenology; we also have figures from the world of culture in order to restore the multidisciplinary approach typical of the Alta Scuola Veronelli and this course.

What role does the Fondazione Giorgio Cini play in this project?

Fondazione Cini is the partner of Seminario Veronelli in this venture and its role is, of course, fundamental, especially for the marvellous location that it is making available, a former Benedictine convent on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, overlooking the San Marco basin: it is a location that denotes our training activity in a significant way.

But it also has a fundamental role for the skills that it manages to mobilise. When we talk about cultural education, the Fondazione Cini is without doubt an authority and so will be fully involved in the promotion of the training actions.

Among other things, the personnel of the Fondazione Giorgio Cini will assist us and be part of the teaching body in the areas that concern, for example, wine, food and Italian art.

Is it still possible to register?

Registration is still open. On the website of Alta Scuola Veronelli, in the “training” section, it is possible to consult the details about the course, the methods of access, and express interest by compiling a brief written interview.

In what way is this course different from similar training activities?

The approach is what differentiates all the training services of the Alta Scuola Veronelli, the willingness to treat wine and agri-food products as part of a cultural heritage. We will make the maximum use of all the training stimuli available in order to train the students in an active way and involve them to the full.

We will cover the sensorial aspect, we will have on-the-spot examples, we will have a body of lecturers who will bring particular points of view: each one will discuss and describe the territories, the people and the wines with a personal, unique and unrepeatable slant, enriching the course with great fascination and great culture.

The authoritativeness of the lecturers is a distinctive factor of our training course compared to other possible services.

How would you summarise the philosophy that underpins the formulation of this training course?

A difficult question to which I immediately answer with a slogan: gastronomy as culture. Gastronomy cannot be separated from culture; culture enriches this vision, especially for those who want to fully learn it, communicate it and master it.

A prerequisite of the Alta Scuola is that of creating an alternative to gastronomy as entertainment, which seems to be the only dimension linked to food and wine in our historical period. We believe that the operators above all must acknowledge their role as active subjects from the cultural point of view and become promoters of a heritage that is immense and that we believe to be still undervalued.

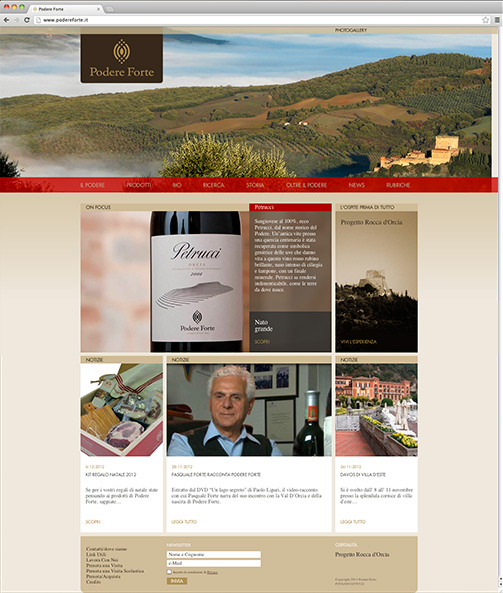

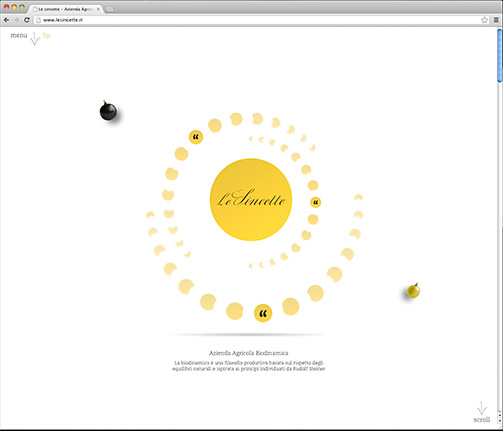

Among the images: logo and coordinated image, invitations, brochures and site created by SGA.

Tag Cultural products, Gastronomy, Global design, Interview, Oenology

The new wine markets through the eyes of Luca Mazzoleni.

How can foreign consumers be won over more effectively? What are the most acknowledged virtues of Italian wines abroad? What communication approach should be adopted to respond appropriately to the evolution of the market? We put these and other crucial questions for those who operate (or intend to operate) on international markets to one of the leading experts in the sector in Italy, Luca Mazzoleni, selection consultant and salesman in the USA for many years and founder of UnoVino Wine Trading, a firm specialising in the brokerage of wine and food products to the main export destinations.

Born in Bergamo in 1975 and having gained familiarity with the world of wine through Luigi Veronelli Permanent Seminar courses, Luca Mazzoleni, after graduating with top marks in Modern History at Milan University, moved to New York for work and remained there from 2002 to 2008. During his six years in the USA with the importer Selected Estates of Europe Ltd, he worked first as procurements manager/selection consultant, and then as area manager and sales force trainer. At the end of 2008, his second USA work permit having expired, he returned to Italy and founded UnoVino Wine Trading, a sole proprietorship engaged in the brokerage of wine and food products to the main export markets. Today, he works with more than thirty companies in Italy and Burgundy, helping them export to North America, North Europe and Asia. In addition to the brokerage activity through his own firm, he previously occupied the position of sales director at two prestigious Italian wine production companies, the Gulfi company in Sicily and the Mazzolino Estate in Lombardy.

Based on your experience, what are the most acknowledged virtues of Italian wines among foreign consumers?

Firstly, the great heritage of native vines possessed by our country, from the north to the south, able to generate an eclectic, all-round wine production, which meets all market segments and tastes. Italian vines offer individual and unmistakable aromas and tastes, and generate a variety of types of wine, region by region, which is equal (if not superior) to the French. Our heritage of expertise in the study and classification of cultivated grape varieties is the main alternative to the organic system of French vines, which have gradually become established in the world to the point of becoming known as “international vines”. A reaction to the standardisation of international vines was already developing at the end of the nineteen nineties in the United States, summarised by the acronym ABC (anything but Chardonnay). Think of fragrant vines, for example, where Italy leads the world for quantity and quality of production: the family of Moscati, that of Malvasie, Brachetto, Traminer, Aleatico, Ruché, Lacrima di Morro d’Alba…these are wines with strong sensorial impact which are currently attracting new consumers in the Asian markets, for example. I remember one episode.. in 2012, I held a tasting of Italian wines at a major food import company in Hangzhou in China. At one point, a young taster among the public said: «I don’t drink wine but I like Moscato d’Asti, it tastes like grape juice».

Secondly, Italian wines are considered to be “wines for dining”, that is, wines particularly suitable for gastronomic combinations, including with exotic cuisines far from that of the Mediterranean. This is due to a very diversified range of aromas and tastes between one vine and another. Added to that, a medium level of acidity, fruity freshness and rather marked sapidity, able to counter the strong tastes of spicy or sweet-and-sour cuisine.

Finally, I think that the evocative power of the “Italy” brand in the imagination of non-European consumers should not be undervalued. Our country is one of the leading destinations for international tourism and nearly every great Italian DOC and DOCG carries with it the memory and image of a prestigious tourist destination, from the Florence of Chianti to the Venice of Prosecco.

Italian wines are appreciated abroad for their many qualities but they have to deal with strong competition. What would enable them to more effectively attract foreign consumers, for example, from overseas?

If, by overseas, we mean the North American market (United States and Canada) or Japan, that is the “mature” markets “worked” for years by our consortia and export managers, then it can be said that the procurement managers of the key accounts in the Ho.Re.Ca sector of the major cities currently possess good or excellent knowledge of our Italian DOC and DOCG wines. Some types of top-of-the-range, high price Italian wine, from Barolo to Pinot Grigio, are today mainstays in any good restaurant or wine store in the United States, Canada and Japan. This result was achieved through the combined work over decades of the consortia, Vinitaly/VeronaFiere, the ICE, the Wine Guides, the export managers of Italian wine companies and their importers and sales managers.

If I think of the early years of the millennium when I was living and working in New York, there were only two major events dedicated to Italian wine in the city, able to attract the cream of the professional operators and American journalists: the Tre Bicchieri Tasting organised by the Gambero Rosso in the old Puck Building in midtown Manhattan, and the Benvenuto Brunello Tasting, the annual presentation of the new vintages of Rosso and Brunello di Montalcino sponsored by the Consortium. Nowadays, there are very many tasting events dedicated to Italian wines in the United States and Canada, sometimes “touring” and held annually, sponsored by the consortia (at least the larger ones with the greatest financial resources) or by other subjects (think of the multi-city Slowfood roadshow and, again, Gambero Rosso).

On the other hand, the major Italian wine consortia organise incoming programmes in Italy reserved to the press and foreign operators, with a well-established schedule of stopovers across the peninsula: I am thinking of Grandi Langhe and Nebbiolo Prima, the Amarone Preview, the Tuscan Previews of Chianti Classico, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and Brunello di Montalcino etc.

Finally, Italian (and even Italian-sounding) catering is widespread in the United States, Canada and Japan and inevitably carries out an action of promotion and popularisation of Italian wines.

If, by overseas, we mean China and South-East Asia, India, South America and the frontier markets of Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia… the situation is very different. Italian catering is not yet widespread and the combined work of communication and promotion of our wines conducted by the consortia or other subjects still has a long way to go.

If denominations or vines are proposed that are little known abroad, how should the communication be approached? In your opinion, is it a good strategy to emphasise their peculiarity or is relying above all on the wine-growing and territorial references a risky stance?

This question is vital and I have a rather firm position in this regard. I am convinced that the communication strategy for our native grapes should be based on their sensorial peculiarities and on the competitive and evocative factors of the territory of origin. I find it anachronistic today to try to make wines of an “international” nature with our regional vines, misrepresenting them and diluting their varietal identity.

Curiosity and open-mindedness are absolutely not lacking in the buyers of quality, both in the “mature” and in the “frontier” markets. In my career as a selection consultant and salesman in New York, I moved pallets and pallets of Grignolino, Freisa, Pelaverga, Uva di Troia, Susumaniello, Carricante, Perricone, Timorasso, Rossese, Moscato di Scanzo etc. and I still sell them today with great satisfaction ... both economic and professional! Note that I do not wish to argue that any Italian wine produced from native vines is, of itself, competitive and commercially viable: rustic wines, inconsistent over the years or without a marked character are always difficult on export markets, be they produced with Montepulciano or with Cabernet. But, for the type of clients that I work with, the values of the preservation of the native, the site-specificity of a vine linked to a unique and characterising terroir, the traditional processes in the cellar and, of course, the environmental sustainability of agricultural practices are crucial values.

We are no longer in the nineteen nineties of oenological “turbo modernism” and the deregulation of wine production, when the imperative was to make a “muscular” wine to earn a good rating from the usual four well-known journalists. It is as if a century had passed: the Internet, blogs and the natural wines movement have radically altered the expectations and the scale of values of all the high-end buyers, from Tokyo to San Francisco. None of the importers with whom I deal would ever buy an Etna Rosso or a Verdicchio di Matelica because I tell them that they have been awarded Tre Bicchieri or 94 points from Parker… only the sad monopolies of Canada still use awards and scores for the rankings of their tenders. When I receive press releases from advertising agencies that work with certain companies and I read about their new wines, I sometimes have the impression that our wine consultants have been left behind by the market. The confusion is understandable, there’s so much wine, perhaps too much wine on the market, in the last twenty years new companies and bottlers have sprung up like mushrooms. I remember my first Vinitaly in 1993 … there were maybe half the exhibitors compared to now.

That said, I must however add that the private initiative of a selection consultant or an importer is not enough to create market recognition for a native vine or a minor denomination. Communicating the typicality of a vine or a denomination can no longer be left to a single company because it would simply be lost in the ether. Effective communication should be done at the producer group level, whether dealing with a consortium (where one exists, is united and works well) or free associations of winemaker friends who share a project, a style and a vision of typicality. And this is a sore point for our winemaking sector, we know it, we are a country of individualists who find teamwork difficult, the splits in so many consortia and the short life of so many export associations bear witness to that.

Finally, the communication strategy for a native vine and its territory should be conceived and personalised depending on the foreign market which it is intended to break into and open up. Not all foreign markets are equally receptive for the Malvasia di Casorzo or for Frascati – let’s say. The first step is to investigate the tastes, cuisine, eating habits and wine consumption in the various foreign markets to which it is intended to export, in order to understand their minimum and maximum potential. And, to do this, what’s required is curiosity, the willingness to travel and perhaps the humility to listen to local professionals able to act as cultural and commercial mediators.

Originality and innovation in the packaging: in markets that often do not have our cultural paradigms, can breaking the rules and proposing unusual labels and formats be a winning formula or can it be counterproductive?

A very stimulating question! The ability to innovate in the graphics and advertising of the wine, even in a debunking and “pop” way, is a feature of the wines of the New World, which had to invent their own new and alternative market space with regard to the wines of the Old World, that is, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Germany etc. Many cellars in California, Chile, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa have rightly focused on the conceptual, the viral logo, the colour, imaginative names and sometimes on outright provocation, not having a tradition and an image established over centuries on which to rely. But the buyers in their twenties or thirties of New York, Shanghai and Singapore with whom I work, who live in ultramodern and multi-ethnic megalopolises and belong to the social network generation, when they think of the Old World they imagine ancient cellars immersed for centuries in a verdant and sleepy countryside, with vines cultivated by generations of the same family, loyal to their own traditions, in an agricultural world on a human scale where time passes more slowly. This may raise a smile but we are exotic for a Chinese person just as China seems exotic to our eyes. I mention China because respect for tradition and the devotion to their founding ancestors are two pillars of Confucianism, which is a kind of state religion for them. This also explains the pre-eminence of Bordeaux wines in China, thanks to the conservative policy of their advertising (have you ever seen a Bordeaux wine in a Burgundy-style bottle?) and labels, all similar and eternally constant: the little drawing of the old Chateau, the avenue through the vineyards, the low wall, the old coat-of-arms of the nobility. Our clients around the world do not see our labels as we see them.

Returning to the discussion about alternative forms of packaging, I always take my cue from my experience in China, which is a really fluid and unconventional market – one might think – that is, not hemmed in by our old world mindset and “Eurocentric” paradigms. It is a market that I know well and I have visited three/four times a year since 2010. If, by “unusual packaging”, we mean a container other than a glass bottle, then I would not be able to point to a success story or a “marketing case history” of any kind. The glass bottle reigns supreme, perhaps with flamboyant innovations like sleeves or unusual shapes, with cloth or shiny inserts, added gadgets or eccentric tops, but always the glass bottle. I have not seen alternative containers such as tins, plastic or tetrabricks, other than on airlines and trains, but that is very much a segment apart. On the other hand, there is the bag-in-box market, which is growing, as in North America and North Europe, and about which a separate discussion can be had.

As a touch of colour … I did once export prestigious old Marsala in ceramic bottles (very popular in China because Chinese rice wine is nearly always bottled in ceramic flasks), but that was an isolated case and a very particular product. So, in my personal experience, including in frontier markets far from the wine culture of the old world, the glass bottle still remains, in 2019, the widely dominant container for quality wines and also for those intended for the mass market.

While the classic 0.75 glass bottles continue to hold the greatest market share by value (72.5%), a recent Nielsen analysis found that, between 2016 and 2017 in the USA, in the major retail chains, the most significant growth value has been that of wine in cans (+59.5%). What do you think about these data? In your experience, can the adoption of an alternative wine package design be a key driver in purchases?

It is significant that the Nielsen survey you mention refers to the major retail chains. In the major retail chains, different rules apply compared to Ho.Re.Ca. segment and the behaviour of consumers is more uninhibited and impulsive, moreover wine is an article on sale among many others and appears less “solemn”, less framed in a traditional wine store image. I have dealt with the American major retail chains like Trader Joe’s or WholeFoods but always and only for wines in bottles.

The main alternative to glass is the bag-in-box, with constant growth also due to the motivation from a certain “ecological” image associated with this format (there is less waste of glass, stoppers, labels, caps), especially in Scandinavia and the rest of North Europe. In this regard, the most interesting phenomenon is that of the bag-in-box for medium range or premium wines and I could cite the case of a famous Langa company whose turnover is mostly based on the sales of good quality Barbera, Dolcetto, Nebbiolo etc. in bag-in-box, for the Norwegian market.

In the USA market, this trend is not yet fully accepted, bag-in-box wines are wines of daily consumption or house wines in restaurants and steakhouses. A typically American phenomenon is that of wines in large 1.5 litre bottles, known also as jug wines (demijohn wines): a diminishing phenomenon in Italy, also in the major retail chains I think, but one that continues in the States and is linked to the nature of the American territory, where the shopping is done in a four-wheel drive and the pick-up is loaded at the back of the wine stores. In my limited experience, I would say that bag-in-box is the main alternative format to glass, much more so than tins or tetrabricks.

How are Italian producers responding to the evolution of the market? Are they tending to stay loyal to glass or trying out new packaging formats in order to compete at the international level?

Trying out new formats and new packaging materials requires capital. If I look at the range of Italian companies with which I work today, only the cooperative cellars or large-scale private bottlers are equipped to handle a bag-in-box line or a Stelvin/Screwcap top. I can understand this, if the demand isn‘t there, if there isn‘t the critical mass to implement alternative packaging, it simply is not done. Producing wine is, of itself, already an activity that requires high liquidity and capital outlay, with medium-long or long-term returns on the initial investment… and most producers are always focused on the investments required in the vineyard and cellar, above all. I understand this, it’s natural.

On the other hand, excellent wines with excellent market potential can be penalised by labels that are inadequate to communicate the message that the wine contained inside brings with it (obvious to the producer but unknown to the operator and the consumer). It is true that the label offers a graphic representation but the specification and core values, the key values that the label must express can only come from the producer. While it is true that Michelangelo painted the Sistine chapel, it was Pope Julius II with his advisors who detailed the “specifications” for the fresco, what to depict and which saints, which prophets and which demons to insert in the various points of the ceiling…

Can an innovative, outside-the-box label influence the perception of a company’s value and reputation and, if so, how?

During my latest work trip to China, a couple of months ago, I saw Terminal 1 of the Pudong International Airport of Shanghai completely plastered with enormous advertising banners of the well-known brand of Champagne, Moët & Chandon, which was promoting, with an ultra-aggressive and “techno pop” graphic, their first Champagne for drinking with ice cubes in it… in white plastic beakers with the Moët & Chandon logo. Just look on Google for “Moët Ice Impérial”; it is both a Demi-Sec and Demi-Sec Rosé, offered in simple bottles with multicolour sleeves. Well …. If a luxury multinational like LVMH today can develop an advertising campaign of this type for one of the French brands with the longest history and greatest prestige, in spite of such a glorious attestation of quality as Champagne, in the premium bubbly section… everything is possible! What would we have said in Italy if one of our major sparkling wine companies had come out with a marketing campaign of this type? Yet none of our bloggers or journalists cried scandal when it came to a name like Moët & Chandon. This is an extreme case and maybe only Moët & Chandon can indulge in this type of shock marketing. I am sorry to sound a little conservative and old-fashioned, but frankly I have become resigned to observing many times that the good old labels of the sixties, seventies or eighties were much more iconic and recognisable than the later ones with sad, minimal and lightweight “conceptual” restyling.

From this point of view, our beloved-hated French cousins are showing that they have known how to do this much longer than us, and to be more aware of the competitive advantages: the tradition, the authenticity, the immutability of a family history. I cannot bring to mind any cases of top companies in Burgundy, Bordeaux, Alsace, the Rhône or Champagne that have radically changed their brand and labels from one day to the next. I would like to see a comparison between the average cost for graphic design and brand development of the average wine production company in France vs Italy... I know, Italy is the home of industrial design, we are all designers, passionate about art and individualistic in taste and style … but I worry every time that a producer tells me: “You know, I’m redoing the labels, they need to be freshened up, I will send them to you soon.” Boom! Firstly, on many markets, labels must be approved and a new label means a new approval: it is extra work for me and my importer. Secondly, I also make clear that, if one day I go to a supermarket to buy Barilla pasta and I no longer see the compact blue mark on the shelf that has always indicated the Barilla packages… it’s easier for me to buy another brand. Packaging that is consistent over time evokes in the consumer that family feeling or familiarity with the brand that the theoreticians of cognitive marketing indicate as a strategic objective to be attained. A lot of consumers are lazy and act with inertia, repetitively… Sometimes, it seems to me that certain producers feel the need to change the labels of their wines out of boredom or to be fashionable, like changing an old car for the latest model or one’s entire wardrobe based on the colour in vogue that autumn. The worst case is when the new graphic livery of the bottle, perhaps developed from a single graphic on which the producer has placed all the responsibility for “renewing the corporate image”, is absolutely anonymous, generically “contemporary” without being able to evoke the territory of origin. Or worse, it can happen that a new label is in clear contrast with the nature and sensorial profile of the wine it represents, and also with the core values embodied by the company. It can happen. Of course, these considerations are valid for denominations and companies with a long tradition behind them, and there are many in Italy. They do not apply to young companies and denominations of origin without an established image.

The best educated, most cultured and brilliant journalist in Italy talks about himself. Interview with Cesare Pillon.

In the preface to the “Manuale di Conversazione Vinicola” (Wine Conversation Manual), the editor-in-chief of the Corriere della Sera, Luciano Ferraro, described him as follows: “Pillon has been writing about wine since the 1970s and is the best educated, most cultured and brilliant journalist in Italy by far.” We interviewed him: he told us about his passion for gourmet food and wine, the origins of his career, the state of specialised journalism today.

Born in Turin in 1931 of parents from the Veneto, Cesare Pillon became a journalist at the age of 21: he began his career at the newspaper L’Unità, collaborating over the years with prestigious titles like the Corriere della Sera and Il Mondo. He covered crime, politics, economics, lifestyle and movie criticism. He has written many published works on the history of the Workers’ Movement.

From 1979 onwards, he focused on gourmet food and wine, penning numerous publications, and is the author of the historical-cultural entries in the Encyclopaedia of Wine published by Boroli; he took part in the Commission that made it possible for Christie’s to organise the first auction of Italian wines. He continues to write about wine and analyse the market in the daily Milano Finanza.

Cesare, you have stated: “I came into the world in 1931, one of the greatest vintages of the last century, especially for the reds. Clearly, wine was part of my genetic heritage, it was written in my stars.” After covering so many subjects for major newspapers, why did you decide to devote yourself to the world of wine?

Because I discovered that whoever makes a great wine, to whatever social class they belong, whatever their level of culture, they are never boring. You can make beautiful cars, for example, without having much of a personality but, to make a great wine, you have to be a great character. This is what fascinated me and made me decide that, as soon as possible, I would only concern myself with wine and gastronomy.

In your early career, up until the age of 48, you covered other subjects. Did this help you when it came to dealing with wine?

Absolutely, yes. Everything I covered, economics, health services failures… it all helped. There is no experience in my life that has not helped me, at the right moment, to better understand wine. My passion for chemistry as a youngster, my interest in history. The history of wine is one of the elements that attracted me the most. It’s part of the human story. You can’t understand human evolution without knowing how wine developed and the relationship between mankind and wine.

What was the work of a journalist like in the years you made your debut in the world of gourmet food and wine?

Newspapers were still composed with lead characters, they weren’t produced digitally. There was no Internet; the news did not come by teleprinters but still by fax. Interviews were done in person, not on the telephone or by sending questions and receiving answers by email. In short, the work was done in a much more direct way. More difficult, more complicated, longer, more effort. But certainly healthier.

What encounters were fundamental for your professional training?

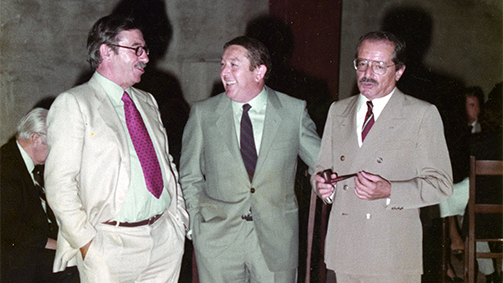

A really important meeting was with Luigi Veronelli. I wrote about is some years ago, telling how it came about and why it changed my life.

I got to know him because I had to ask him to do an article on wine for Il Mondo; he couldn’t because he had an exclusive contract with Mondadori but he gave me all the help he could. Once published, he encouraged me, my publisher, Paolo Panerai, and all the winemakers he knew to help me continue on the path of gourmet food and wine.

When I met Gino, it was as if I had known him for years: I had always read everything he had written. I never managed to compile a proper archive of my publications, but I did with what he wrote. All his columns in Panorama, glued on strips of cardboard and properly listed. Seeing him in person seemed to me simply to be deepening an old acquaintance.

What did the opportunity to take part in creating the Encyclopaedia of Wine mean to you?

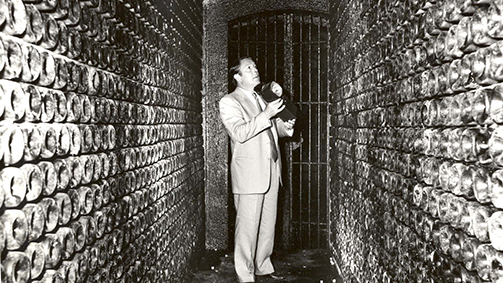

After 25, perhaps 30 years from my debut in the field of wine, it was an opportunity to take stock of all this experience. I realised at that moment that, by a stroke of luck, I had witnessed the renaissance of Italian wine because I had begun in the years when it had reached rock bottom. From that point, the only way was up. So it was, and here I am.

Is there some episode in your career that holds a special memory?

I remember very clearly one episode right at the start of my career in gourmet food and wine. I was making a survey of Montalcino when I met Count Costanti: he had all the traits that some years earlier I would have detested. He was a nobleman, an aristocrat, he had been a local party chief during the fascist period… And yet we got on so well I finally realised: labels are worthless, men must be judged as individuals. From that moment, I began to fight against intolerance. I had never been intolerant, but from then on I was certain that intolerance is truly the worst feeling that a man can have.

Cesare Pillon with Giacomo Bersanetti

You have written for many newspapers and publishing houses. How do you think the relationship between the press and journalism and the world of wine has changed and at what point do you think it is today?

I am very worried because there are symptoms of an attitude that is no longer healthy, no longer right, no longer tolerable. The truth is that there has been a democratisation, if you like, of the world of wine. The Internet now makes it possible for small companies to communicate directly with journalists; generally, they do it through public relations companies, which have multiplied out of all proportion.

Once, press releases were issued for really important event; they were sent by teleprinter or by post to specialist journalists, imposing an embargo in order not to disadvantage the last person to receive it. It was a complicated, long and costly business.

The Internet has made everything easy, and now I receive everything, including press releases asking for the publication of insignificant news in a questionable, if not offensive way. I find this deterioration very unpleasant.

At the end of the 1970s, when you began to cover gastronomy and oenology, these subjects were not “mainstream” as they are today. Do you think their wider dissemination is an advantage for the sector or do you think it is a case of overexposure? What does all this mean?

It is very true that there is overexposure. I had the good fortune to collaborate with newspapers edited by Panerai who was very sensitive to this issue and encouraged the publication of articles on wine at a time when this was very unusual.

But now, it’s all become too much. Everything comes down to the tasting: in 80 per cent of cases, communication focuses only on that.

I have always tried to tell the stories of the men of wine, the men who make the wine. I am convinced that the fundamental factor for great wines is the Cru, the selected vineyard, but the man who cultivates it is crucial. In my work as a journalist, and not only in the field of wine and food, I have always been convinced no one gets enthusiastic only about ideas. What interests them are stories about men. It is through the stories of men that ideas catch on. This is well understood by today’s populists, who deliberately use fear to get support for their ambitions.

How has the link between the world of wine and the world of finance changed since you wrote the first edition of the wine guide for executives in 1979?

We had drawn up this publication for a section of the economic weekly Il Mondo entitled “Personal Affairs” because it was intended for those managers, business people and readers who were personally interested in the subject.

Now everything has changed: there have been cases of wines sold en primeur, there are wine investment funds and, above all, there is interest now in investing in wine and therefore in auctions. I must say, however, that so far I am still the only Italian journalist who continuously reports on the auctions in Milano Finanza.

You have been a member of the Journalists’ Association for more than 50 years. Over this period of time, the profession of journalism has changed radically. What challenges do journalists in the sector face today?

Today’s journalists face major problems posed by the Internet, which is taking all the advertising. The successful outlets are the ones provided free to users via the Internet, but they are the slaves of advertising. This is not healthy.

The challenge that today’s journalists must overcome (and I don’t envy them) is not simple because, in reality, the phenomenon, like all human phenomena, has two sides: one is very positive, the democratisation of communication, the fact that everyone can take part. But there’s a negative side. And I must say that journalists are perhaps those with most to fear. The fact that copyright is not recognised (the attempt to ensure payment has already provoked a reaction from Trump, who argues that it is an attack on the very foundations of the United States) is really worrying.

Has the language of gourmet food and wine criticism in Italy changed over the years? In what way?

Yes, it has changed: the fact that everyone can take part has certainly lowered the level. We are a long way from the days when Gino Veronelli was involved, a man of boundless culture, or Mario Soldati, characters who wrote the most important literary works on wine. Currently, it has certainly all been dumbed down. But I think this is a transitory phenomenon. Any form of democratisation begins with a lowering of the general level before rising again.

Every year, you compare the scores of the main Italian guides, yet you say you “have never given ‘votes’ to wines”, and in the past you have expressed your agreement with Gualtiero Marchesi, when he disputed the “claim of giving an objective opinion expressed on the basis of personal taste”. What is your position on the scores given by the gourmet food and wine guides?

The gastronomic guides are not currently thriving, they are definitely in decline. They are no longer the consumer’s Bible and this, I must say, is a positive aspect of the advent of the Internet.

With regard to the question of the scores: I have tried to humanise them, comparing the scores of all the guides in order to obtain a collective consensus on one wine rather than another. But I have always considered giving scores to a wine a little arbitrary. A wine is appreciated for the emotions it can convey. And the emotions vary depending on the time, depending on who is tasting it, depending on what they are used to. It is too personal, in short. Certainly, there are great wines of indisputable importance for everyone, for whoever loves wine, and wines that are less important. But it is a long stretch to say that this one is worth 99 and this one is worth 97.5.

Carla & Cesare Pillon.

When you approach a wine, what are you looking for, what do you hope to find?

New emotions and unusual personalities are what strike me. The world of wine is very rich in this regard: truly extraordinary people, friendships that spring up around a bottle. It is difficult to establish such an intense relationship with a teetotaller.

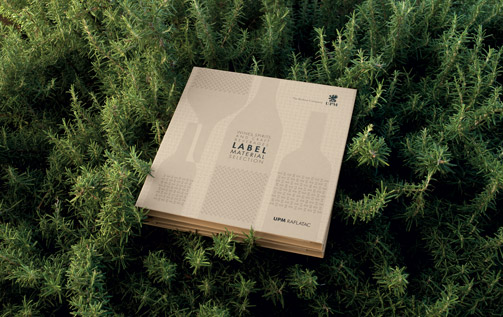

Design of new catalogue for UPM Raflatac’s self-adhesive labels

UPM Raflatac is one of the world leaders among self-adhesive label manufacturers. It supplies high-quality paper and film both for consumer and industrial products through a global organisation made up of factories, distribution terminals and a widespread network of sales offices employing around 3,000 people.

The production of a new catalogue for self-adhesive labels used for beverages - considered a crucial segment for the company’s growth targets - led UPM Raflatac to strictly focus on certain objectives:

- to raise and consolidate the perception of the company’s reputation to bring it into line with the objective quality in terms of aesthetics and technology represented by the materials in the portfolio;

- to demonstrate, especially in the target format of drinks’ producers, designers and printers, that UPM Raflatac is completely aware of and able to respond to all their needs and expectations;

- to convey its identity and its values, based on the utmost concern for the environment, production sustainability and a high level of technical expertise.

These are well-defined, complex objectives that needed to be conveyed through authentic, innovative content; creative solutions were required both to excite and stimulate the curiosity and imagination of the interlocutors and to demonstrate the potential of each label selected, for the purpose of reinforcing the perception of reliability and versatility through high-profile performance.

All the decisions connected to the design of the new catalogue, both the part dedicated to the assortment and the visual book, had to be in line with the corporate philosophy, its values and production methods and so our responses were drawn from observations of the extraordinary, boundless beauty of Nature.

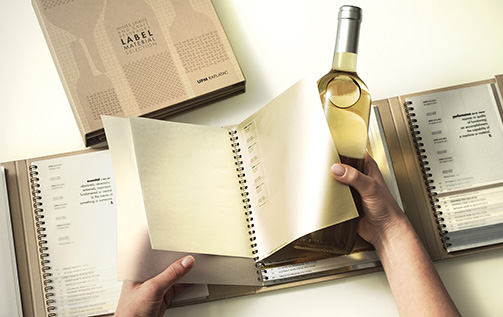

The new UPM Raflatac catalogue was designed to be very practical and easy to consult; when looking for a label, the whole range must be available at the same time and “on first sight”. Just this simple aspect can enable the catalogue of one label stock manufacturer to stand out compared to another.

The samples as ‘listed’ in two directions: horizontal (for instant identification) and vertical (to enable selection by touch and sight).

The labels were carefully selected to meet current and future trends in the beverage sector in the various forms, ranging from artisan drinks to spirits (cognac, vodka, whisky) through to soft drinks, beers, wines (whites and reds) and, of course, sparkling wines. Alongside the assortment, only the essential information was included to enable the features of each label to be recognised instantly.

The catalogue’s structure was devised to optimise the use of material and display the company’s great concern for the environment; unlike most catalogues of the sector – and others – plastic was not used but, instead, a material that conveys a sense of naturalness and warmth right from the first contact and, at the same time, possesses resistance, in view of the frequent use by the operators.

The self-adhesive labels offered in the catalogue’s four sections are the real protagonists of this new work instrument and that’s why we avoided needless enhancements.

The real ‘meeting’ between a group of 18 different labels – selected depending on the corresponding beverage type – and design creativity comes in the visual book, the catalogue’s fifth section.

The design of this section started with an examination of the performance of each label, arising from the close dialogue with UPM’s technicians and experts. In the second phase, 18 samples were chosen, for which an intervention was needed to enable the intrinsic features of each material to be highlighted.

This had to be done in a way consistent with the codes and languages of each market segment and in an especially distinctive way: specific concepts were identified for each project – all inspired by Nature – that were pertinent and innovative, creative and incisive, surprising and memorable at the same time.

Content and a harmonious and linear direction of reading were required, which could be defined as holistic: from the type of drink to the label identified as most suitable, from the name assigned to the product to the creative visual which, for each label, is never generic but always significant.

In all phases, from design to actual production, the dialogue with UPM’s managers (Italian and international) was constant, as it was with the company (MCC Lucca and Prato) that printed and produced the catalogue; only the close, continuous exchange and discussion of every detail enabled its optimal production.

The new positioning of Mirabella through a global design strategy project

Strategy /Brand value building

In an increasingly competitive context like the world of wine production, the strategic management of the brand is seen by some producers as a primary requirement. The identification of the positioning, therefore the value-bearing system, the mission, the key target and the content of the storytelling are fundamental and determinant steps in defining a consistent and effective strategy for obtaining positive, long-lasting results. For the Mirabella project, the analysis phase was crucial: with Claudio Castellaro (Creative Business), it was possible to explore, based on a methodological approach perfected through numerous shared projects, the various aspects that contribute to determining the personality of this specific corporate organisation; in particular, its potential in terms of brand value building through marketing guidelines aimed at the consistent development of all the communication instruments required for its relaunch.

Currently, priority actions have been carried out but the strategic guidelines prefigure a more extended and complex course that will be carried out in the medium period.

Branding

The project phase firstly led to the restyling of the Mirabella corporate symbol. The face of the goddess Demeter was redesigned, giving a more contemporary character to its reinterpretation. A new, more personal symbol whose three-dimensionality was determined by the positive-negative contrast of the two sides of the face, the graphical synthesis of which enabled the problems of reproducibility evident with the previous brand to be eliminated. The action on the brand also led to the redesign of the corporate name, stylistically harmonised with the figurative symbol with improved legibility.

The new brand ensures attribution and continuity with the previous one and required the introduction of a radical change in the appearance of the products.

The development of the brand was further broadened with the creation of an image handbook in which the codifying of the rules of application and the chromatic codes ensure its correct use over time. The creation of the corporate coordinates completed the definition phase of the primary instruments of corporate identity.

Naming

An important element that determines the identity of a product, especially a wine, is its name. But creating a new name, consistent with the image of a cellar that is not already in use is today truly one of the hardest tasks. “Edea” was created with the intention of affirming, in a simple and easily memorised way, the character of this Franciacorta, the wine that constitutes the core business of the cellar and that distinguishes it, since the fining on the lees lasts for more than 30 months, while 18 would be sufficient under the regulations for making a Franciacorta.

Packaging

In relating to the new positioning of Mirabella, oriented towards innovation and to the main key target identified, the Millennials, the appearance of the products was designed with the precise aim of conveying the values associated with the brand, such as naturalness and innovative capacity.

The three forms that make up the label are a precise reference to the stones in the territory of Franciacorta, the natural forms of rocks smoothed by water, an element of particular importance for this company, since the underground cellar is surrounded by groundwater that maintains its temperature and humidity always constant.

The three ‘stones’ which, by varying in composition and colour, characterise the various wines, can also refer to Teresio, Mirabella’s founder, and his two children, Alessandro and Alberto, respectively the company’s cellar master and marketing director. Three wine experts whose different skills and attitudes contribute to the creation of these Franciacorta with a unique personality. The simple graphical language and the strict minimalism convey the particular attention that the company pays to aspects regarding the naturalness of their wines, a firm commitment that led this cellar to produce the first Franciacorta free of sulphites.

Secondary packaging

The enhancement of a sparkling product cannot neglect the development of a distinctive secondary packaging, consistent with the strategic direction and the image of the wines, as well as their respective positioning, while also carefully considering aspects such as functionality and costs.

Catalogo

The renewal of the image of a cellar must pay particular attention to the images that document its life, the place and the people at the times that mark the different activities and production phases. We therefore planned the involvement of photographers and video operators who put together – under our artistic direction – an accurate record that, as it is enriched over time, will make up a complete archive of the life of the cellar. The images and video shots communicate authenticity and naturalness, without force or artifice. The material gathered was selected with this same objective, avoiding any retouches or alterations to the result obtained. From this material, we were able to create the Mirabella catalogue project which, in relation to the new orientation, portrays the character of the cellar with freshness and dynamism.

Web Site

Special attention was given to the new Mirabella website, created in collaboration with NokNok, which was conceived as the primary vehicle for the contents of value that characterise this cellar. Video tutorials and a detailed information system seek to express the particular attention paid by the cellar to the passionate and expert consumer but also to all those who seek to broaden their level of knowledge. Thanks to the experiential communication and the dialogue with its interlocutor, aspects that characterise the company, such as protecting the environment and nutritional health, are thereby made transparent and accessible. Indeed, it is Teresio and his two children, Alessandro and Alberto, who tell us, in a personal and direct way, about the cellar, their experiences, their expectations and their wines. The Charter of Ethics completes this information, represented through a dynamic infographic – inspired by the process of growth of the plants – that encapsulates in a single image the constant effort poured into the various areas through the actions undertaken by the company. Special attention was also paid to the choice of the content, the terminology and the technical choices in order to achieve the best optimisation for the research engines.

Tag Brand, Global design, Packaging, Website

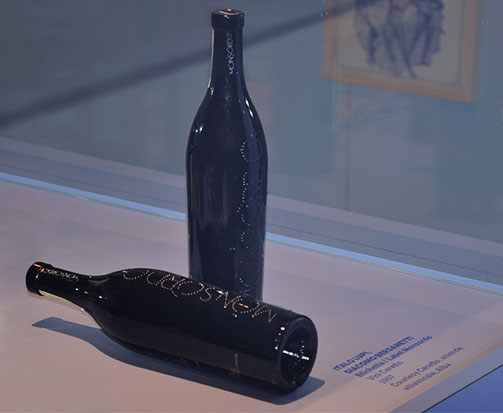

"Comete" Alois Lageder - Organic wine project

With the new “Comete” line, the winery Alois Lageder introduces a group of wines obtained through a series of innovative research and experimentation projects. The aim is to raise awareness of the enormous potential waiting to be expressed in the wine-growing heritage and the versatility of the land, but also to face the inevitable change in climatic conditions, by testing unconventional grape varieties suited to warmer climates and exploring pioneering winemaking techniques.

All the while, the research never deviates from the holistic philosophy that the winery has applied since it introduced organic-dynamic agriculture – one of the first to do so in Italy.

The packaging had to convey a series of concepts: from the highly innovative content, to the experimental character and the unrepeatable nature of each of the wines, the constant dedication to quality, respect for the environment and for the vineyard, which is treated as a living entity and not simply a means of production; and finally the care for the people, whether they be the partners that have provided grapes for generations or the passionate consumers for whom these wines are produced.

The name ‘Comete’, as well as being an explicit reference to the company symbol, clearly communicates the purpose and meaning of these wines, produced only in highly limited quantities. The comet indicates a direction: it can have a brief or an extremely long duration, but it leaves a trace, an indication of a path along which to proceed.

The graphic identity of the line couldn’t simply be coherent with the company identity: it had to express the evolution in progress and it had to do it in an immediate and unconventional way.

The adoption of a single wraparound label simplifies manual application: the blue background – Lageder’s institutional colour – is evocative of cosmic space and accommodates the gesture (a reference to its handcrafted quality) that distributes the pigment and traces the comet. All aspects of production were analysed with care, including the sequence: a single type of paper for the white and red wines, which ensures stability even when in contact with water and ice, that is natural and expresses preciousness, and that above all offers a surface to which the colour adheres permanently.

The pigments used (red and white) are made of natural ingredients, are quick drying and offer high stability, making them perfectly suited to the manual operations of the packaging.

Every bottle, then, is characterised by a comet, each different to the next, and at the end of the packaging process, is numbered to underline its uniqueness.

Tag Organic wines, Packaging

Gruppo Italiano Vini – Italian Organic Project

The new Italian Organic Project of the GIV, Gruppo Italiano Vini, aims to optimise communication of the organic wines of these selected wineries. For Bigi, Castello Moncaci, Melini and Rapitalà, we designed new packaging that guarantee each label a precise identity, personality and recognisability as a product of their respective wineries.

The aim was also to create an identity for the line through their shared aesthetic criteria and by introducing a symbol to mark the organic products offered by the group.

For each label, spontaneous and light illustrations were used, characterised by fresh colours that express vitality and authenticity.

For Rapitalà, a brightly coloured butterfly symbolises the health of the habitat; for Castello Monaci, blades of grass represent the technique of allowing plants to grow between the vines then turning over the soil to naturally reintroduce the nutrients. For Melini, a ladybird, symbol of agriculture in which chemical pesticides are not used; and finally, for Bigi, a cross section of a vine illuminated by a ray of light evokes the influence of the celestial bodies on planting times and the life cycles.

Tag Organic wines, Packaging

L’Arena: Amarone on the trail of Ulysses, 700 step up to the challenge.

Excerpt from the article by Camilla Madinelli: “L’Amarone sulla rotta di Ulisse, alla prova si cimentano in 500”, published in L’Arena, July 2017

The myth of Ulysses, from his adventurous journey over seas and far off lands to his multiform intellect, even after thousands of years, still enchants and teaches designers, winemakers, and sailors of the new millennium take on new challenges: the challenges of the future, but with a regard for the past. The Homeric hero was adopted as the leading theme at Cantina Valpolicella Negrar’s award ceremony for the Limited Edition label «Wine Mythology Label» for the Amarone Vigneti di Jago 2012 Domìni Veneti. The winning label, from the Slum Design Studio in Florence, came out of the international ideas competition «Wine Mythology Label» promoted by Code “COmpetitions for DEsigners) in collaboration with Cantina Valpolicella Negrar and with the technical partnership of UPM Raflatac and Grafical. The competition, coordinated by the winery’s public relations manager, Marina Valenti, saw 700 submissions from designers and artists from 40 different countries. The union of wine and design, therefore, seems to be more popular than ever. Especially if we then add a mythological element. And even more so if Ulysses is involved. «Designing a label and creating a wine have much in common with the figure of Ulysses», explains the wine designer, Giacomo Bersanetti. «it takes subtlety in invention, the courage to shift one’s point of view, curiosity and the ability to convey authentic contents of value. The winning design, with the talent of extreme synthesis, uses colour as light: it is highly evocative and invites a lover of Amarone to establish a more intimate experience with the wine».

To put oneself to the test, for many, is an adventure too good to turn down. There is the risk of shipwreck, just like Ulysses. It happened to Matteo Miceli, entrepreneur, boat maker and sailing enthusiast, on his way back from his third solo regata in 2015. The wreck cost him the keel of his Eco40, his hi-tech boat equipped with solar panels, and water and wind turbines that allows him to travel in an eco-friendly way. A Verona-based carpentry specialist, Dmz of Villa Bartolomea, managed to repair the damage and restore the vessel. And so Miceli, as he revealed at the winery, is ready for his latest adventure: Ocean World 2019, a round the world trip while being self-sufficient for food and energy (complete with on board vegetable garden and chickens), in a regata with other solo sailors like himself. Ulysses’ mythical journey is still so enchanting that the scholar Giorgio Conti, cofounder of the Sustainability Archives at the University Ca’ Foscari in Venice, confessed to having retraced the journey when he was younger. Remaining with his feet on the ground and in the terroir, finally, is the enologist and general manager of the Cantina Valpolicella Negrar, Daniele Accordini, judge of the competition: “The intelligence of Ulysses”, he concludes, “is an intuition that lets him read reality in an adaptable way and to find new solutions to any problems: in winemaking, it is the intelligence to find the weak points in the production system and change them, adapting tradition.”

Tag Press

Label Art: the laws of organization of visual information - Part 2

In the second part of Label Art, organised by the association “Gli Ergonauti” and Maria Teresa Tonutti, Paolo Bernardis, researcher in the field of visual perception and cognitive neuroscience at the University of Trieste, and Giacomo Bersanetti, designer and founder of SGA Wine Design, talk about the principles on which our perceptive system works before complex visual information.

When we recognise an object in a visual scene and give it a name, our brain has carried out a series of processes that allow it to establish that certain parts of the scene belong to the object while others belong to the background or other objects.

For example, in the famous image of the Dalmatian by the photographer R.C. James, it isn’t easy to distinguish which black marks are the dog and which are the background; and yet once the silhouette has been recognised it is impossible not to see it again.

Or in the image of the panda, the famous symbol of the WWF, where does the white of the head end and the white of the background begin?

And in Rubin’s paradigmatic vase, what object is depicted? The vase/candelabra or two heads facing each other?

Our perceptive system uses principles or rules (also known as laws of segregation/unification) to decide which parts of an image are part of the object and which are part of the background. These principles, described for the first time by the Gestalt school psychologist Max Wertheimer (1880-1943), can be summed up as follows: (a) principle of proximity, objects close together tend to be grouped into units; (b) principle of similarity, elements that look similar tend to be grouped into units; (c) principle of common fate, elements that move in unison tend to be grouped into units; (d) principle of objective set, united elements tend to maintain unity; (e) principle of good continuation, elements tend to be organised in groups that require the least variation in the perceived contours; (f) principle of closure, information is organised into elements that generate the perception of closed edges; (g) principle of past experience, the observer favours organisation of information influenced by previous knowledge.

These principles involve a ‘ceteris paribus’ (all other things being equal) clause; in other words, the factor in question will affect grouping between the elements only when other factors are equated between elements.

The validity of Wertheimer’s observations is confirmed by a great many subsequent observations, using probabilistic models (Kubovy, 1994). Most perception researchers today agree that Wertheimer’s laws work because they correspond to statistical regularities of the environment and the objects that populate it.

The relationships between art and science are well known and have can be traced back many centuries. We only need think of Leonardo da Vinci for example, and of his painting influenced by his study of anatomy and physiology. To cite an example from our times, a scientist particularly dear to me and who also painted, is Gaetano Kanizsa. Kanizsa was an internationally famous academic, founder of the Triestine school, and made fundamental contributions to the study of perception and the psychology of cognitive processes in general. “Kanizsa’s triangle”, invented in 1954, has become a universally recognised symbol of research into visual perception.

But Gaetano Kanizsa was also a surprising painter, and into his painting, not without irony, he poured his interest for the “creation” of images, as he had the chance to write when he participated at the 10th Biennial of San Martino di Lupari, 1990*. An app* dedicated to Kanizsa can be downloaded at the following link: https://itunes.apple.com/it/app/kanizsapp/id1038839202?l=en&mt=8

PAOLO BERNARDIS

Below are a selected examples of design projects inspired by Wertheimer’s laws of perceptual organisation.

Cesari - 2004

Michele Chiarlo - 2014

Cascina Castlet - 2008

Cesari - 2010

From the catalogue “Moltitudine di impronte” 2002, published by his daughter Silvia Kanizsa.

App created by Paolo Bernardis, Walter Gerbino, Carlo Fantoni, Studio trart and Provincia di Trieste

Label Art: a coming together of research, design and production - Part 1

Label Art, an event organised by the association “Gli Ergonauti” and Maria Teresa Tonutti, brought together Paolo Bernardis, a researcher and expert in visual perception and cognitive neuroscience at the University of Trieste, and Giacomo Bersanetti, designer and founder of SGA Wine Design, to discuss and explore the relationships between research, design and production.

This encounter was conceived in the spirit of reducing the distance that has always existed between the worlds of business, university and society. The aim was to stimulate a dialogue between who conducts research to produce knowledge, specifically regarding our minds and on the brain, and who uses this knowledge to produce a product, the label of a wine bottle, that communicates with the consumer as effectively as possible.

The visible information that reaches our eyes is processed and transformed to create representations of the outside world in our minds. These internal representations (or perceptions) are formed according to functional principles or models of cognitive processes. The models of perception are not limited to explaining how the mind functions, but seek also to explain how they can be implemented in the neural mechanisms of our brains, or rather, functional models of the groups of nerve cells that form the brain.

The perception of the outer world

The study of perceptions poses us some preliminary questions that can help us understand the very nature of the study of perception. Kurt Koffka (1886-1941), one of the founders of the school of Gestalt Psychology, in The Principles of Gestalt Psychology (1935), asks: “Why do things look as they do?”.

The question might seem strange. The simplest answer is that the world and its objects are here present and appear this way (red, soft, big, hot,…) because in reality they are that way. This type of approach is called naive realism, and if adopted, does not get us very far towards discovering how our perceptive mechanisms work. Another approach is critical realism, which argues that things look as they do because the organisation of information imposed by the mind/brain system is what it is. In other words, it is the organisation intended as the laws and functioning principles of the mind/brain system that make us experience things as red, hot and soft. There are many examples that demonstrate how naive realism is wrong.

In the example of “Kanizsa’s triangle”, we see a central white triangle with one of the angles pointing directly upwards, the white of which is lighter than the white of the background.

Kanizsa’s Triangle – MODAL COMPLETION

In reality, no such white triangle physically exists, only three black circles with “slices” missing. This example shows us how we “see” the white triangle not because “it is here present”, but because our mind/brain system works in such a way that makes us “see” the white triangle. Several years after this illustration was proposed by Gaetano Kanizsa (1913-1993), two researchers (Grossberg & Raizada, 2000) proposed a functional model of the nerve cells of our brain that explains why, thanks to a sophisticated systems of excitatory and inhibitory connections, in the illusion of Kanizsa’s triangle we see the white central triangle, even though it doesn’t exist.

PAOLO BERNARDIS

Below is a selection of projects inspired by the perceptive phenomenon of “modal completion”.

Fontanafredda - 2006

Gialdi - 2012

Winzenberg - 2016

The label as the primary vehicle of storytelling

If we look up the meaning of “history”, we find it defined in terms of “research, investigation, and cognition”, that is well defined activities and concepts that naturally evolve into “knowledge” and “vision”, underlining how “knowledge” and “observation” are closely correlated.

If we look up “story”, on the other hand, it is interesting to read that it is a “composition… generally dedicated to a single event and intended to be read uninterrupted, distinct from a fairy tale as it tends to represent facts as they actually occurred.”

A fitting description, then, of the core activities and characteristics of storytelling, a term that has become popular today and is now essential to all businesses that are mindful of their own unique values, roles and objectives. The importance now attributed to communicating content in order to initiate, nurture and consolidate a dialogue with one’s customers – both existing and prospective – stems from the realisation that the messages and the unidirectional way of communicating that businesses used in the past were schematic and superficial. In a word, communication was ineffective and, above all, failed to take into account the fact that people want to be an active part of the business-customer relationship.

Naming e packaging

There is no product or industry that is unsuited to storytelling, however the wine industry is certainly among the most privileged sectors for its historic and profound affinity with the creative and intuitive faculties of the mind and, consequently, with culture. As Luigi Veronelli once put it so beautifully: “Wine is consumed for this miracle. It drives intelligence to greater things.” And in the story of wine, in the recounting of its personality and its values, the label on the bottle continues to be the protagonist and does most of the work in what can be a series of coherent communication activities and languages. To contextualise these concepts, we’ve selected our recent project with the Produttori Associati Moscato d’Asti, intentionally avoiding experiences with private producers with which, by the way, we have been applying the same methodological approach for around 35 years. The project began with an in-depth analysis and research that would allow us to identify the contents and values on which to construct the new identity. A strategic analysis allows us to define the design direction and positioning, but also other aspects such as pricing and distribution strategies, and the content and tone of the communication.

Mario Berchio, enologo Natincò

The name of the wine had to express the collective character of the initiative and its ambitious purpose: a large association of grape growers and winemakers who decided to create a wine that would become a landmark producer for its type through the perfection of a well-defined productive method. In logical relation with the name chosen, Natincò, the image represents a group of people singing in a choir creating harmony and at the same time, expressing the particular production method used for this Moscato, which involves the selection of grapes from the high, medium and low altitude hills, assembled during vinification to obtain the best possible quality.

The label shows an elegant, refined choir, in accordance with the characteristics of the wine, and at the same time evokes Italian musical tradition that, most universally recognised and with its highest expression in opera. An additional and highly characteristic aspect is the colour, adopted for its distinctiveness, memorability, and immediate evocation of the fresh and floral perfumes of the wine. All of these elements of content contribute to creating and expressing a sense of uniqueness and originality through a sensory structure that each observer interprets individually, from different perspectives, influenced by their own cultural traits, their personal sensibilities. In order for storytelling to be effective, it is essential that the emotive content and authenticity are tangible and easily perceptible, this is one of the reasons why we used the real produces as models. The winemakers of Moscato participated with enthusiasm, openness and humility to create their own communication tools.

All consequent communication, in its various forms that range from the website to a series of viral videos, from advertising to the classic trade folder, stand and digital presentation, responds to a principle of coherence that guides and accompanies the design of every tool so that they all work together. As Jung so astutely describes: “the observed moment is the sum of all ingredients”.

Comunicazione integrata e immagine coordinata

Tag Global design, Packaging

Wine Tourism and Hospitality: An analysis by Carlo Pietrasanta - Part two

The mission of the Italian Wine Tourism Movement is to promote the culture of wine through wine tourism and develop synergy between the different players. What stage is wine tourism at in Italy? What works and what doesn’t? Why is it worth it? All the answers to these questions on wine tourism and much more in the second part of the interview with Carlo Pietrasanta, President of the Italian Wine Tourism Movement (part one HERE).

Intervista a Carlo Pietrasanta, Presidente Movimento turismo Vino: Un’analisi su Enoturismo e Marketing dell’Accoglienza - Seconda Parte from SGA Wine design on Vimeo.

How would you define, or describe, wine tourism?

Wine tourism is the greatest opportunity the world of wine has seen in the last 25 years. It has self-generated with the epochal change in mentality: a quarter of a century ago, talk of wine tourism and winery visits was almost heresy; today there’s hardly a winery in Italy that doesn’t offer tourist services.

What it’s history in Italy?

Wine tourism in our country developed after a 1992 study by the University Bocconi that highlighted how, despite a high demand to visit them, Italian wineries were mainly closed to the public. Since then, a group of winemakers, captained by Donatella Cinelli Colombini, a producer of Montalcino, came together and began planning activities linked to wine tourism. The first activity we invented was “Cantine Aperte”, that is Open Wineries, with the first edition held in 1993.

To what extent can wine tourism function as a direct sales channel? Do you have any data on direct sales that result from wine tourism?

We have wineries with up to 50% of their revenue accounted for by direct sales through wine tourism. Direct sales at the winery have always been a part of distribution, and in the 1970s a lot of unbottled wine was sold. Nowadays, another type of direct sale prevails, bottled wine, with a greater profit margin.

When selling wine directly from the winery, what’s the average amount people spend? How many wines to they take away?

The average oscillates between 3 and 6 bottles, depending on the area and the value of the wine. If the bottles are prestigious the average is around 3 bottles; for mid-prices wines (around 8 euros), they often take away 6 – 12 bottles.

What proportion of the total revenue does this represent?